Salting the earth

The impact of salinisation

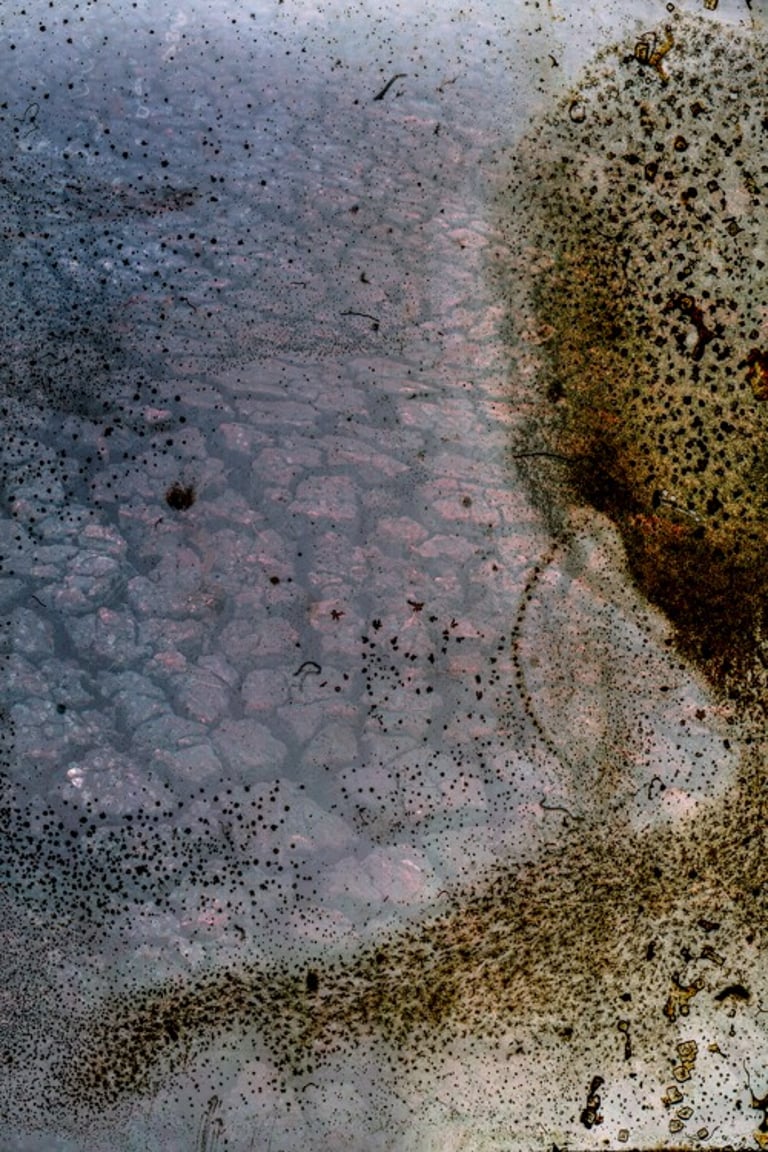

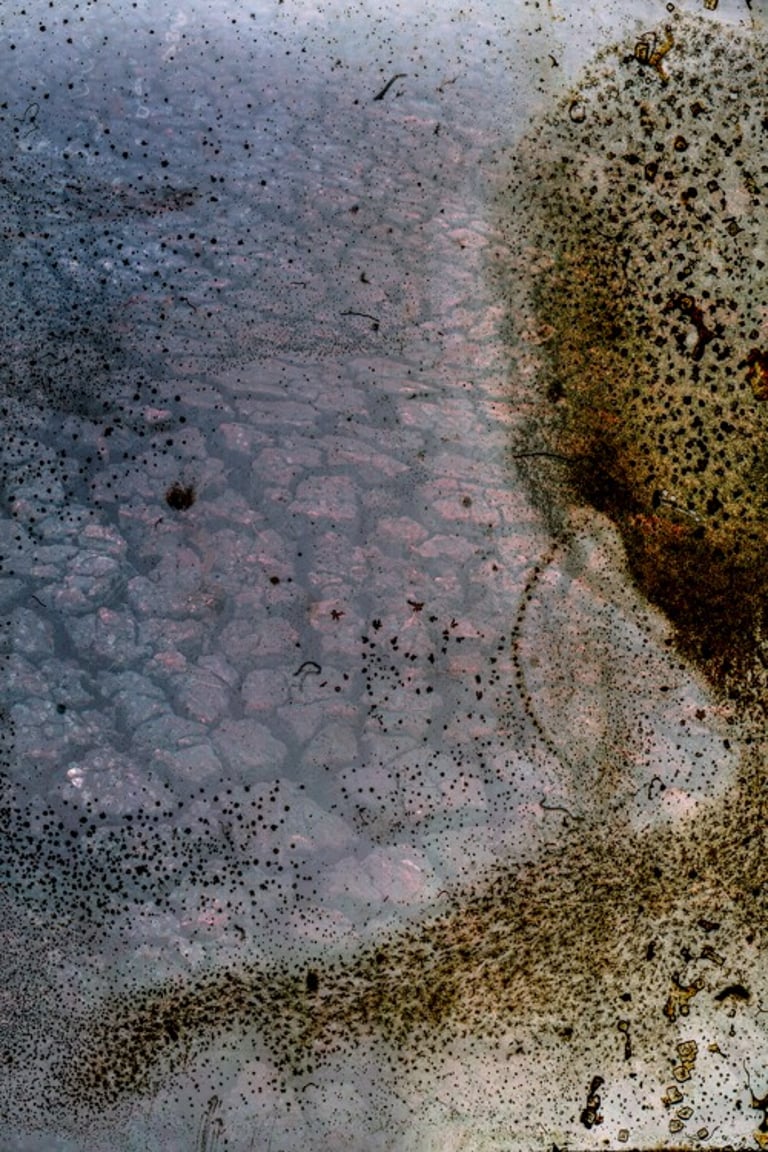

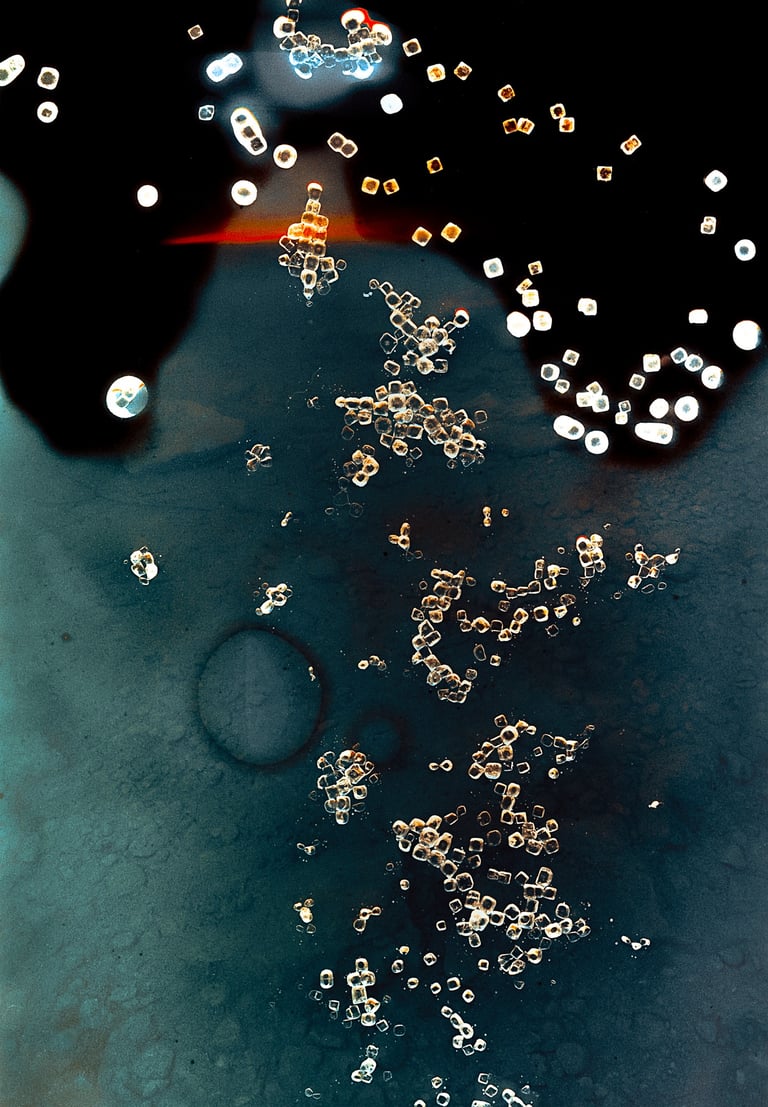

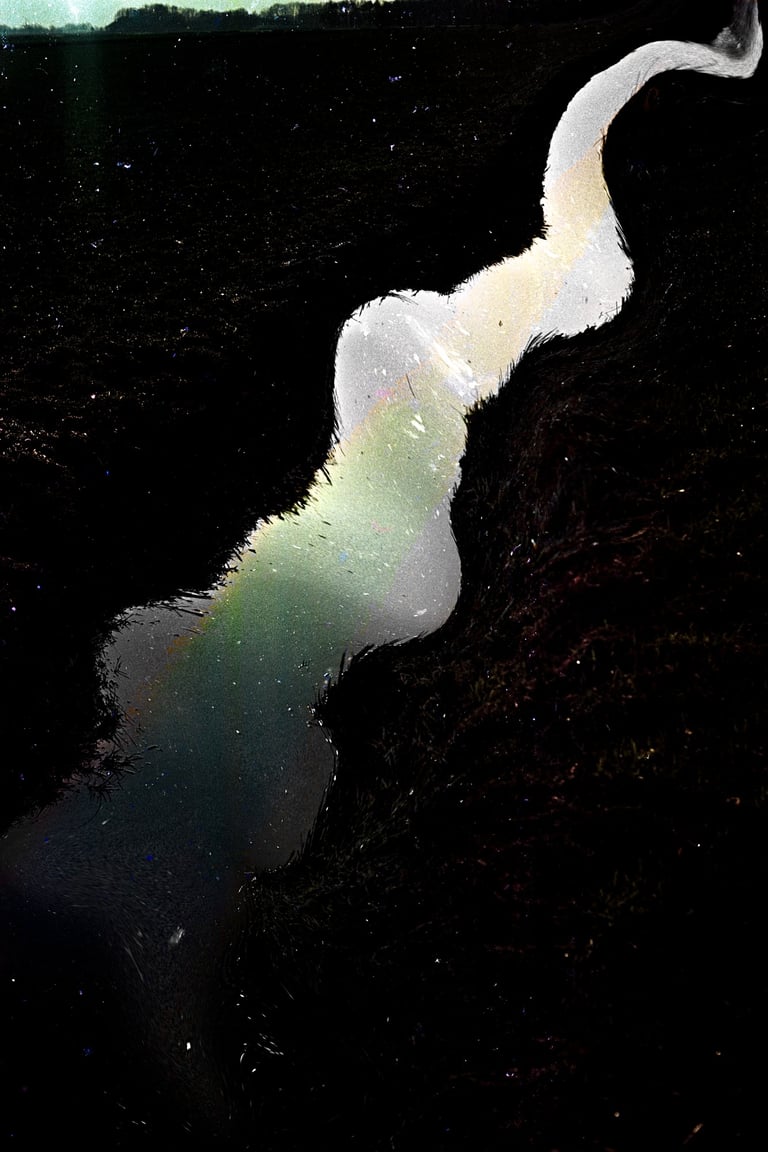

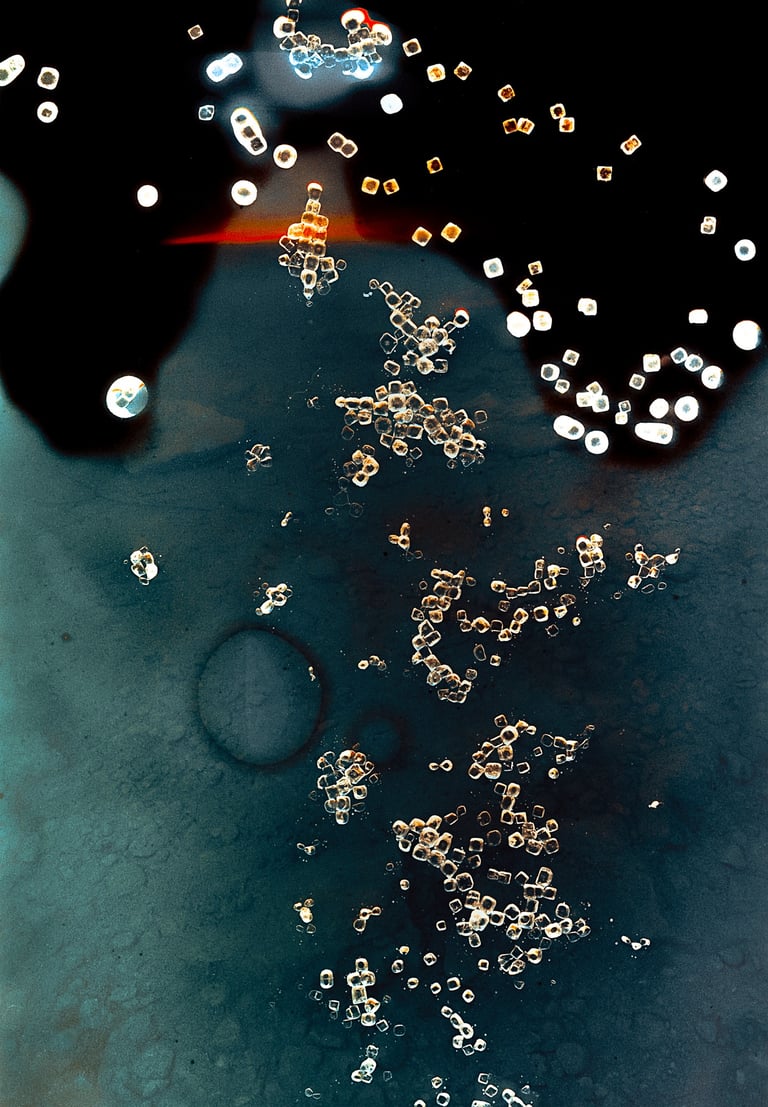

Table salt and vinegar, still promoted as eco-friendly herbicides, have a devastating impact on the soil where more than 60% of all organisms live.

My nearly blind mother accidentally poured vinegar on her newly purchased crate of violets. The plants wilted immediately. A similar process is increasingly occurring on a global scale as a result of climate change and agricultural practices.

An estimated 1/5 of the world's agricultural land is affected. Salinization creates new deserts and has consequences for the food production of an ever-growing world population. In biblical times, salt was used to destroy a community.

Technique: collages with analog images, interventions during scanning of lumen prints, cyano lumens, cyanotype, and film soup.

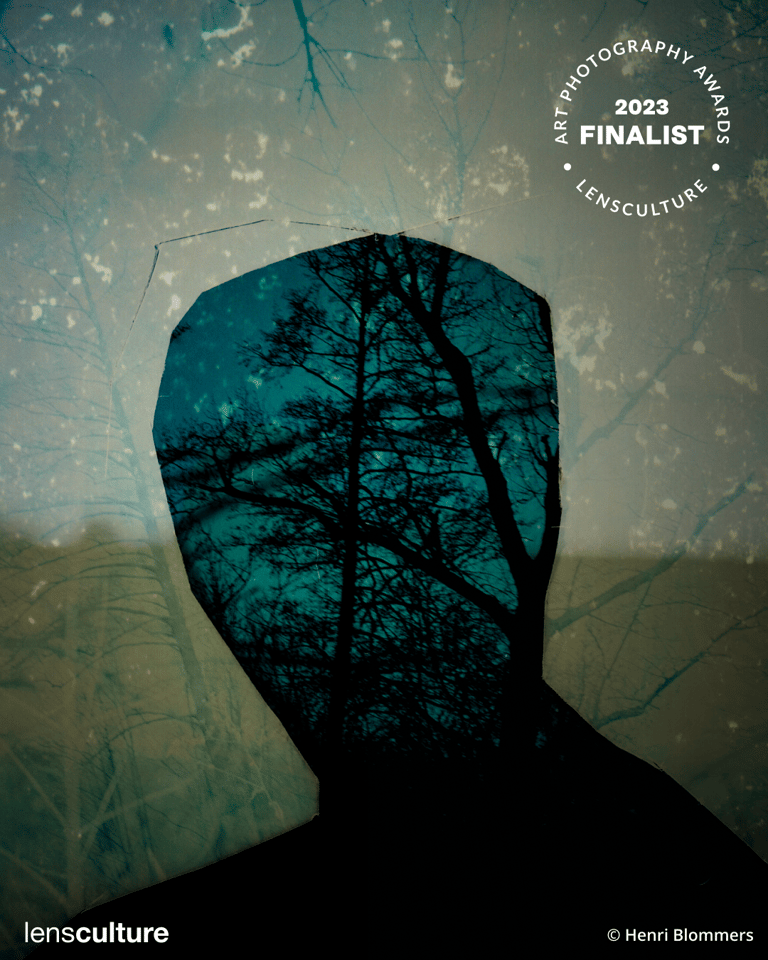

Homo Reconnectus

Possibilities to restore our connection with nature

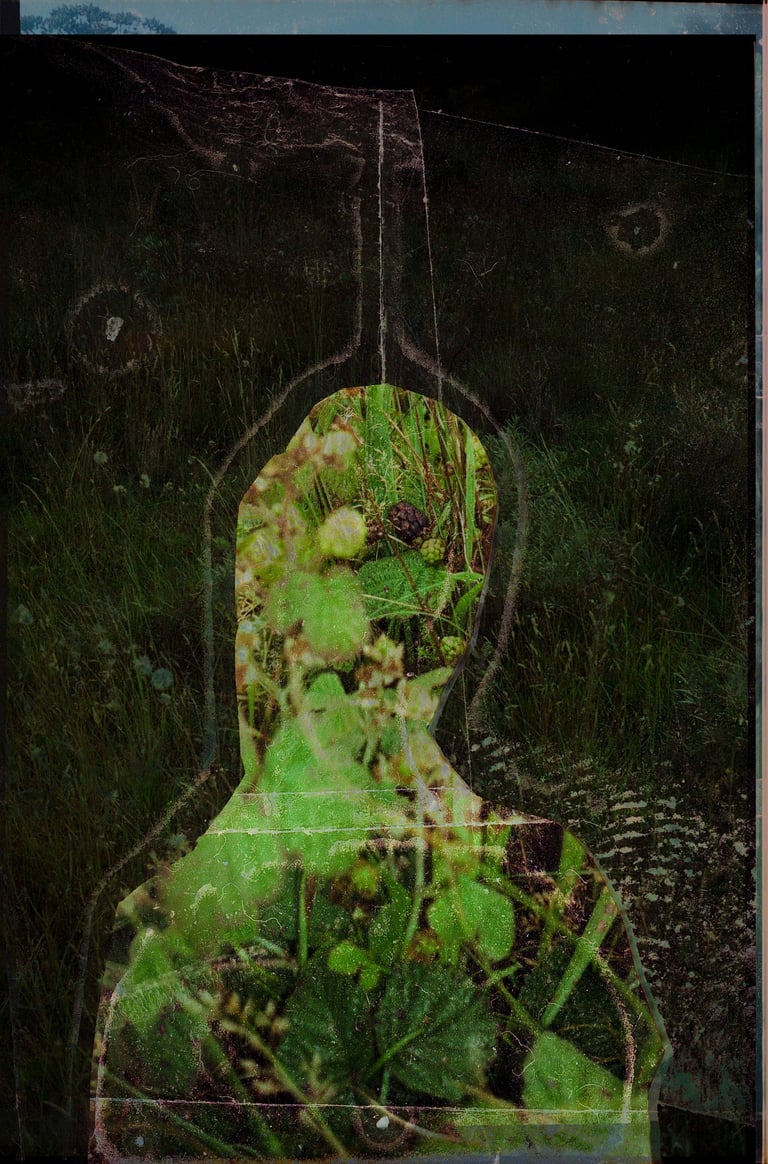

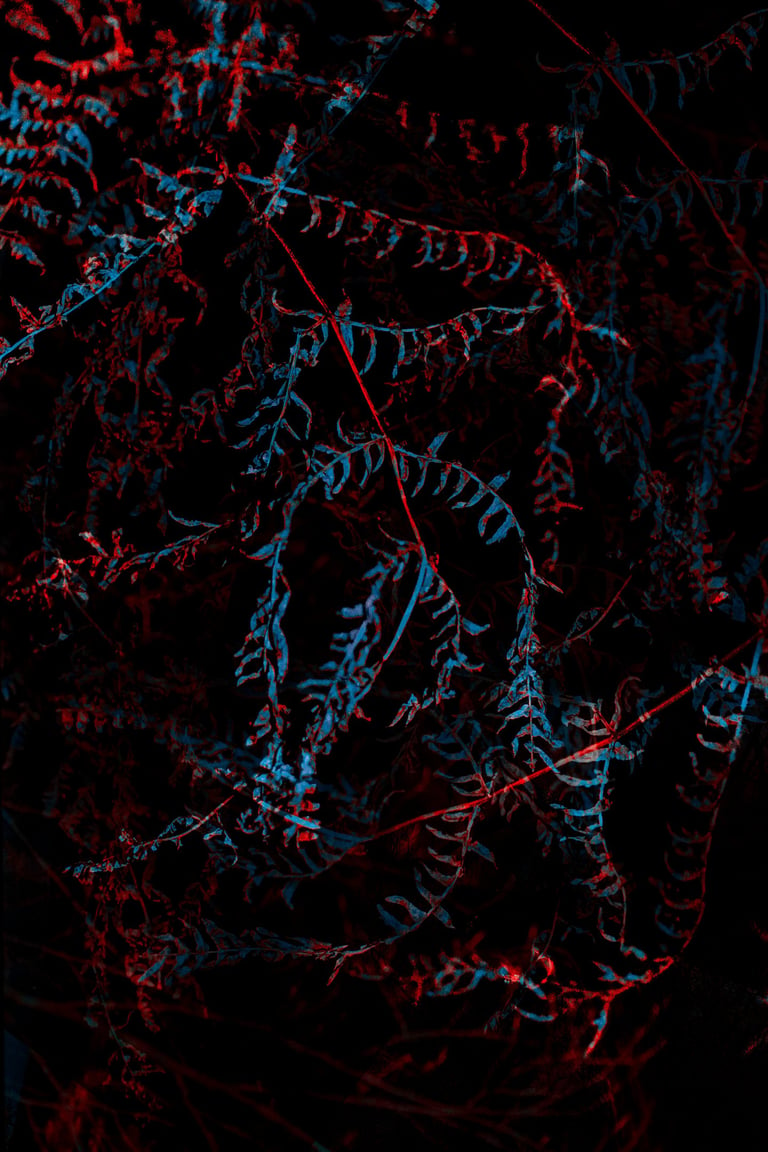

Regeneration is necessary if we want to overcome the climate crisis. We can achieve this by implementing regenerative agriculture (traditional farming without chemicals, artificial fertilizers, and concentrated feed) and reducing cattle so drastically that they are only grazing for nature management and living on residual flows. The reduced methane and nitrate levels will result in soil impoverishment leading to improved biodiversity.

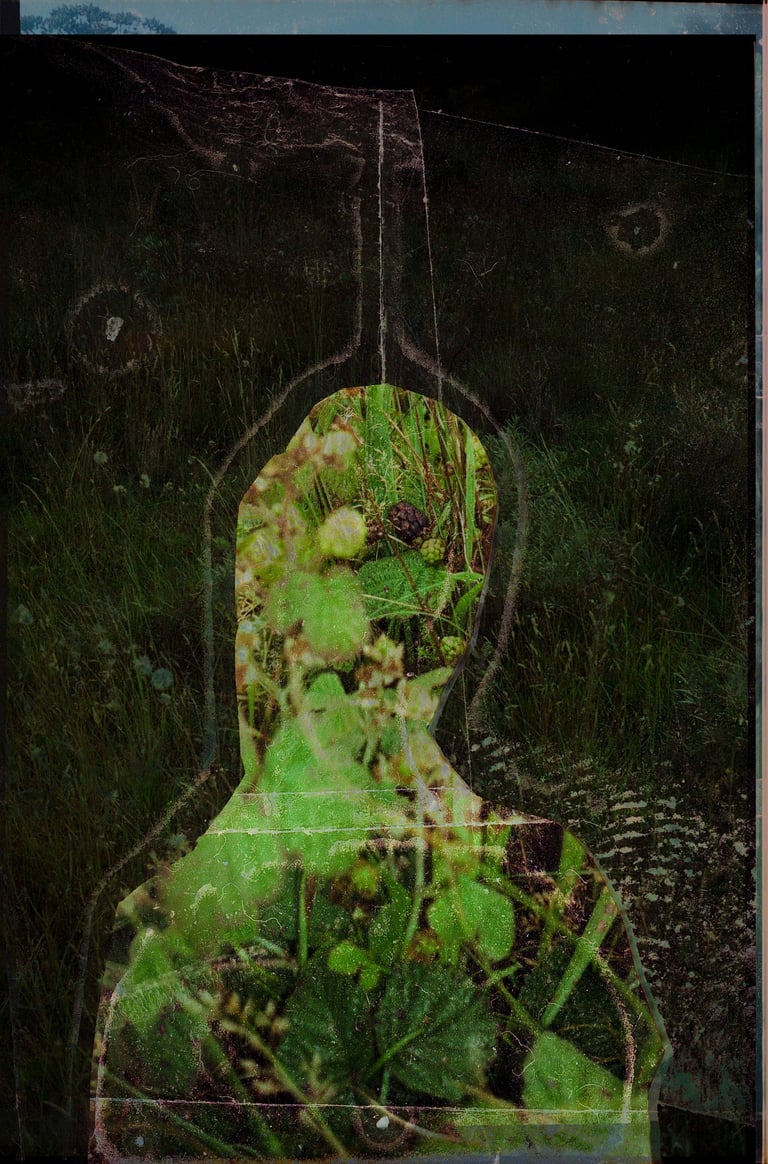

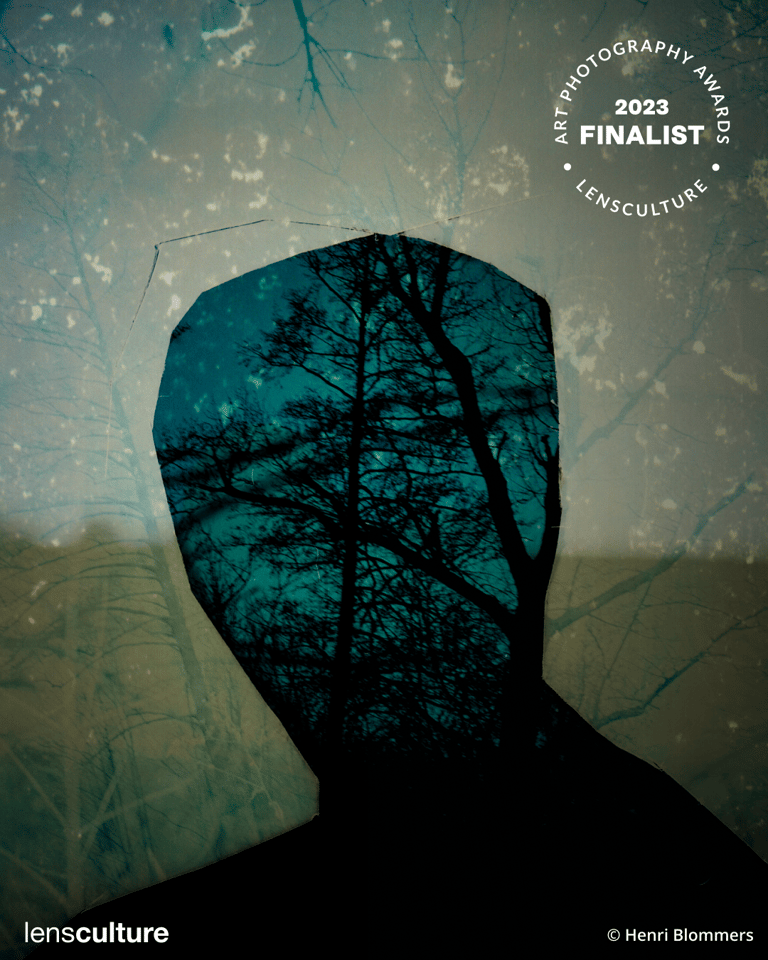

We can improve the basis even more drastically by connecting loose pieces of nature, such as forests, meadows, and gardens, enabling plants and animals, now blocked by roads and other human obstacles, to find their species for mating. Also, the concept of ownership needs to change: our garden is not our property. We are only its temporary stewards. Chaos is good, not the controlled black earth stony garden that is the common ideal now. Our human perception that nature starts beyond the fence of our garden needs to change. Education and re-prioritization are fundamental if we are to become part of nature again. To be part of the pyramid and not at the top, a new type of human, Homo Reconnectus.

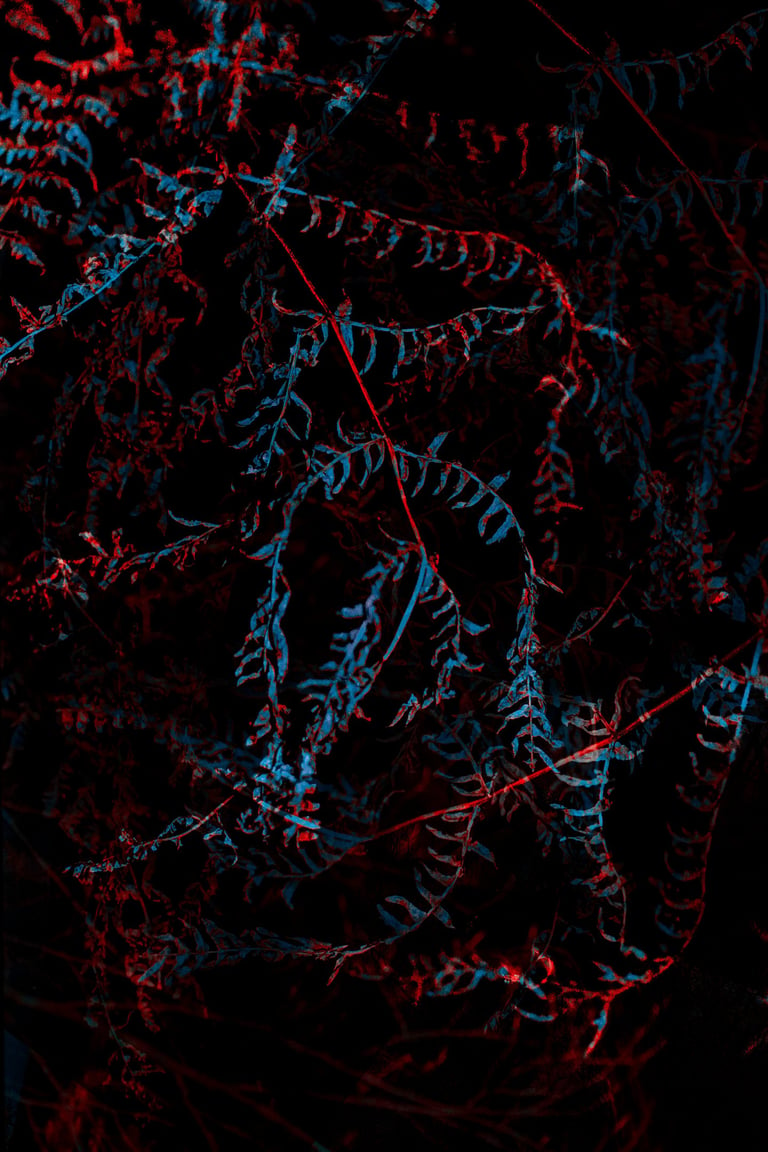

Technique: Analog images developed in water from rivers in agricultural areas and boiled with plant remains of invasive or proliferating species due to climate change. The negatives were then treated with glyphosate, fertilizer, nitrogen, ammonia, and biological pesticide or incorporated into analog or digital collages.

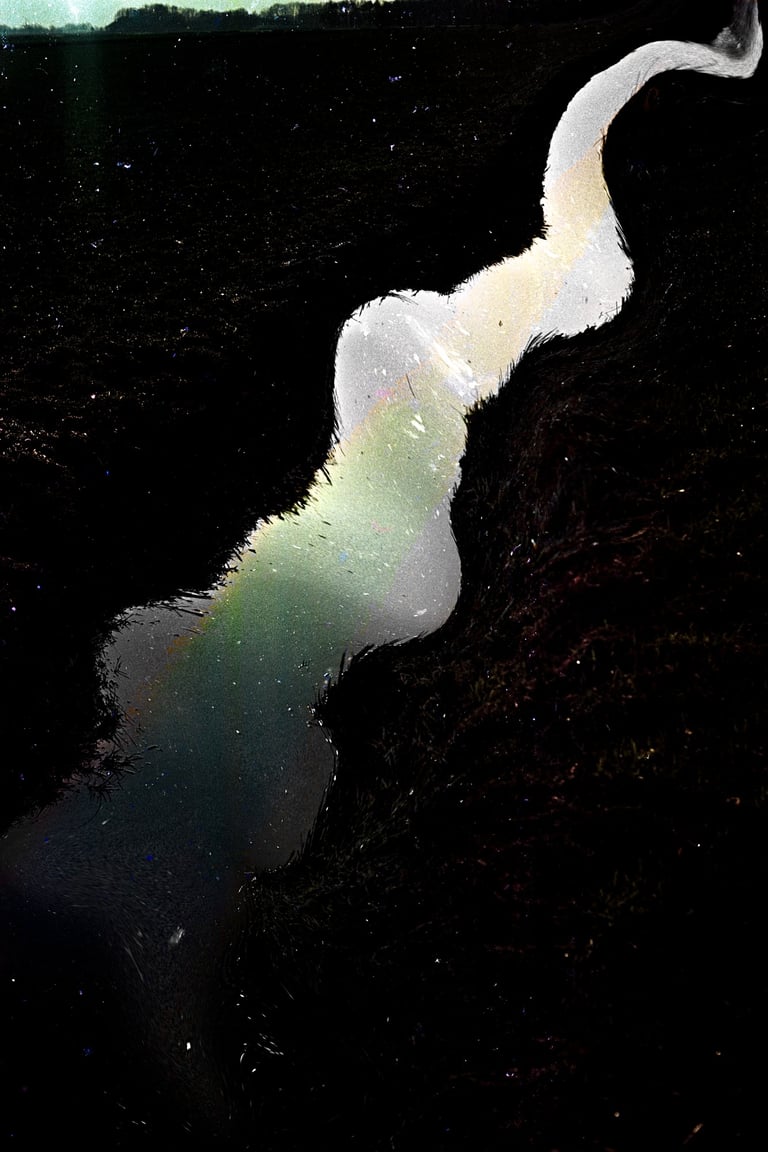

Plastic Utopia

Absorbtion ability of nature

We are living in the Anthropocene: the geological period when humans are thought to have the biggest impact on the planet's climate and environment. Plastic waste from the 1970s still washes up on our shores completely intact; the plastics that do decompose simply fall apart into smaller particles. Scientists are not sure how long it will take for this detritus to dissolve—or whether they will ever disappear.

“Plastic Utopia” is a photographic project on the impact of our consumption on the environment. My hope is that nature will be strong and flexible enough to persevere. The series is also a reflection on my own behavior—my photographic waste.

I worked with three other artists—all from other disciplines—to investigate this environmental situation. We decided to go into the field and do research in a pseudo-scientific way. For example, we visited seemingly clean areas—parks and beaches—where I made ‘inventory’ images of the refuse we found. That was the beginning of “Plastic Utopia.” After a while, I started placing my findings back into nature and taking photos with the future in mind. I eventually started to incorporate objects that might not yet be considered waste, like abandoned toys.

I wanted flash to play an important role in highlighting and isolating certain parts of the frame, so I decided to shoot this project digitally. I also wanted the colors to be strong—almost like a commercial product shoot—so I relied on post-processing to shift the colors and give the images a more futuristic feeling.

I considered the aesthetics of this work very carefully. Some of my previous series had really dark, almost muddy images. I felt that people were not looking at them. I had long discussions with my artist friends about this. Often viewers disengage from work that is important but also ubiquitous—when you talk about politics, waste, or environmentalism, sometimes people disconnect because they are inundated with information.

In “Plastic Utopia,” I wanted people to see both the beauty of nature and the beauty of trash. I also wanted the audience to ask questions about my approach: am I making it too beautiful, too aesthetically pleasing? Perhaps I am, and yet perhaps this is a good way of forcing people to reflect on the subject.